TranceAddict Forums (www.tranceaddict.com/forums)

- Political Discussion / Debate

-- Artistic, Intellectual and Philosophical Influences & Recommendations

Artistic, Intellectual and Philosophical Influences & Recommendations

Since there's already a books thread (or sticky rather), and I thought we could use another one to expand discourse on PDD. Everything goes; authors, writers [not sure if I'd call graphic novel story writers authors or not], intellectuals [inside and outside of academia], artists [of any type, from comedy to music and acting], movies, documentaries (hopefully ones that are true to the objective nature of one), music... anything but [specific] books a sticky already exists for that. I'm not sure if this is sticky worthy, so we'll leave that decision up to our friendly neighborhood mod Lira. I guess it would be fair to include things such graphic novels as they don't exactly fall in the category of conventional reading material. Note, by music I mean Records [read as Music CD or albums] that are not EDM as the site already has more than one sub-forum dedicated to it. So feel free to post away.

Minimal Suggestions & Guidelines to Make Your Post More Informative & Accessible to Interested Readers

)

) )

)

Here's a sample template similar to the one I used that you can quote for formatting convenience if you like:

code:

>> name << ( >> birth_date - death << ) [IMG] >> image_link << [/IMG] " >> quote << " - >> name <<

- Alias: >> Alias <<

- Profession: >> Profession <<

- Biography: >> Bio << [ Source ]

- Additional Links: [ Official Site ] [ Wikipedia ] Wikipedia Excerpt: ""

- Recommended works:

- >> title <<: >> embedded video / streaming audio <<

- >> title <<: Amazon Link

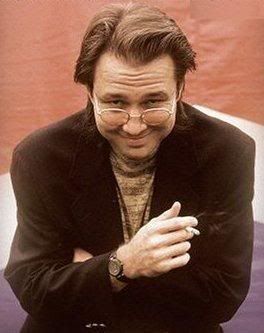

Bill Hicks

(December 16, 1961 – February 26, 1994)

“Today a young man on acid realized that all matter is merely energy condensed to a slow vibration, that we are all one consciousness experiencing itself subjectively, there is no such thing as death, life is only a dream, and we are the imagination of ourselves. Here’s Tom with the weather.” -Bill Hicks

In junior high school, Bill met Dwight Slade and they became fast friends. Together, the two spent hours creating comedy routines. Bill and Dwight’s ambitions of performing in front of an audience seemed hopeless. Even though there were no comedy clubs nearby, they made recordings and sent them to local agents. One package earned them an overnight slot on the Jerry Lewis telethon, but they were underage and couldn’t perform. Finally and opportunity arrived when the Comedy Workshop opened in Houston. Chauffeured to the club by friend Kevin Booth (the only one of the three with a driver’s license), they convinced the club manager to give them a shot. Bill & Dwight became the venue’s youngest regular comics. With only a handful of performances under their belts, Dwight’s family relocated, leaving Bill to focus on his solo act.

Shortly after graduating high school, Bill moved to LA to start the first phase of his love/hate relationship with the city. Performing alongside then-unknowns Jay Leno, Jerry Seinfeld, and Gary Shandling, Bill found the going rough. After two years he had had enough and returned to Houston. Although his experience in the heart of the showbiz beast had been disappointing, Bill remained enthusiastically dedicated to stand-up comedy. He began touring, relentlessly, building a small but loyal base of fans.

In 1984 with the support of Jay Leno, Bill appeared on David Letterman’s show for the first time (at the time of his death, Bill had performed on the show eleven times). He began playing more prestigious rooms and fellow comedians developed tremendous respect for his work. Hicks tried again to integrate into traditional showbiz by moving to New York which he found more agreeable than LA. There Bill stopped taking drugs, a habit he had picked up during hard years of touring. Although he attended AA meetings, Bill never renounced his drug use, explaining in performances that he had “some great times on drugs.” This blunt honesty flowed over into other areas of his performance and Bill addressed a variety of subjects with new, pure clarity.

Bill’s comedy (despite his own claims to the contrary) was not about hate or pessimism. Bill was an unabashed optimist. He believed that most people were good at heart but evil forces were deliberately distracting us all from creating a better world using television, lies, tobacco and alcohol as opiates. Bill felt a revolution of thought was coming and that it was his duty, as an emissary of the truth, to bring whatever light he could to anyone who would listen. This blunt, straightforward expression of these ideas could cause clashes with less enlightened, unsuspecting audiences. The result was sometimes dangerous; Bill had his ankle broken and a gun was pointed at him on stage. Despite these experiences, he refused to compromise his material and soldiered on.

His first standup comedy video, Sane Man, was recorded in 1988 before an enthusiastic crowd in Austin, Texas. Much of the material heard on his later albums is here in the embryonic stage. Bill toured the clubs even more incessantly in the early 90’s, playing 250-300 gigs a year. Although he loved performing, he hated traveling. But the effort was showing results; his legend was spreading by word of mouth. His first comedy album, Dangerous was released in 1990. That year Ninja Bachelor Party was released on VHS and HBO aired an all-Hicks episode of One Night Stand. At the Just For Laughs Festival in Montreal, Bill was a hit with audiences and critics.

Soon after his Montreal gig, Bill debuted in the United Kingdom appearing in an American comedy revue. British audiences enthusiastically embraced Hicks (Bill joked that it was because of his pale skin), and he toured the country, extensively, winning the prestigious Critics Award at the Edinburgh Comedy Festival. Bill’s second album Relentless was a developmental step from Dangerous but still only hinted at what is to come. On a 1992 English tour he filmed the Revelations performance video. Although he was working harder then ever and his career was building momentum, Bill was still not reaching as large an audience as he had hoped. Meanwhile, other comedians were breaking into mass consciousness with a watered-down version of Hicks’ comedy. While it would have been lucrative for Bill to tone down his act and supersede these pretenders, he had no interest in doing so. Uncompromisingly Bill moved forward, expanding his world-view. Turning his back on the opportunity to cash in, he plowed ahead fearlessly. Bill’s material and performances evolved at a tremendous rate.

In 1993 a breakthrough seemed closer than ever. Rolling Stone had declared Bill “Hot Stand-Up Comic” of the year. He began work on “Counts of the Netherworld” a high-concept talk show for British TV. He had been nominated for Stand-Up Of The Year by the American Comedy Awards for the third time. He wrote a column for the British humor magazine Scallywag and was asked to write for the political journal The Nation. Rock bands flocked to his banner; Radiohead, Rage Against the Machine and Tool professed their admiration. He had been invited by the New York Public Library for Performing Arts to speak at Lincoln Center in June of 1994. Performance films, screenplays, books and CD box sets were in various stages of discussion. Perhaps to take advantage of this synergy, Bill moved back to LA.

Then, in June, Bill learned he had cancer. Choosing to keep his illness a secret, he told his family, a few close friends and went straight back to work. In August of 1993 Bill’s brother Steve flew to LA and together they packed Bill’s belongings into his jeep and drove to Little Rock, Arkansas where Bill moved into his parent’s home. He had already recorded both Arizona Bay and Rant In E Minor, with ambitious plans to mix music that he had recorded into the performance to compliment the comedy themes. He described the conceptual Arizona Bay as his Dark Side Of The Moon built around the theme of LA falling into the Pacific Ocean. Throughout the year, Bill underwent chemotherapy on a weekly basis. The tour dates didn’t let up and his writing pace accelerated.

In October, Hicks taped a performance for David Letterman that became on of his most infamous moments. Returning to his hotel following the early evening taping, Bill was told that censors had cut his segment. In a 39-page letter to John Lahr of The New Yorker, Bill expressed his frustration. He had reason to be enraged; the set had been approved (twice!) by the powers that be. It would’ve been his last television appearance. His last gig was on January 6, 1994 at Caroline’s in New York City – he did not complete the series of shows.

Despite his illness, Bill was at peace. He spent time with his parents, playing them the music he loved and showing them documentaries about his interests. He called friends to say goodbye and re-read J.R.R. Tolkein’s Fellowship Of The Rings.

On Saturday, February 26th, 1994, Bill died. He was 32. [ Source ]

[ Official Site ]

[ Wikipedia ]

Wikipedia Excerpt:

"Hicks tended to balance heady discussion of religion, politics and personal issues with more ribald material; he characterized his own performances as "Chomsky with dick jokes." [2]

2. Shugart, Karen. "Bill Hicks: 'Chomsky with Dick Jokes". Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Retrieved on 2006-03-03."

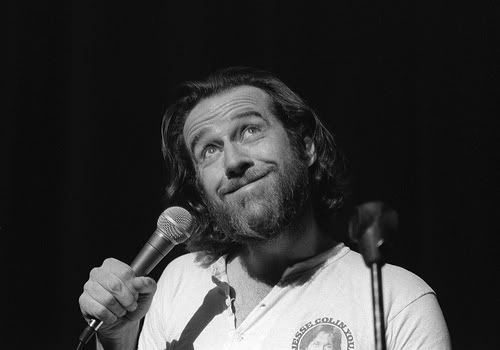

George Carlin

(May 12, 1937 – June 22, 2008)

"I'm completely in favor of the separation of Church and State. My idea is that these two institutions screw us up enough on their own, so both of them together is certain death!" -George Carlin

[ Official Site ]

[ New York Times Article ]

[ Wikipedia ]

Wikipedia Excerpt:

"George Denis Patrick Carlin (May 12, 1937 – June 22, 2008) was an American stand-up comedian, often considered one of the best of all time. He was also an actor and author, and won four Grammy Awards for his comedy albums.

Carlin was noted for his black humor as well as insights on politics, the English language, psychology, religion and various taboo subjects. Carlin and his "Seven Dirty Words" comedy routine were central to the 1978 U.S. Supreme Court case F.C.C. v. Pacifica Foundation, in which a narrow 5–4 decision by the justices affirmed the government's power to regulate indecent material on the public airwaves.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Carlin's stand-up routines focused on the flaws in modern-day America. He often took on contemporary political issues in the United States and satirized the excesses of American culture.

Carlin's themes have been known for causing considerable controversy in the American media. His most usual topic was (in his words) humanity's "bullshit", which might include murder, genocide, war, rape, corruption, religion and other aspects of human civilization. He was known for mixing observational humour with larger, social commentary. His delivery frequently treated these subjects in a misanthropic and nihilistic fashion..."

Miles Davis

May 26, 1926 � September 28, 1991

" My future starts when I wake up every morning... Every day I find something creative to do with my life." -Miles Davis

Miles Davis was one of the greatest visionaries and most important figures in jazz history. He was born in a well-to-do family in East St. Louis. He became a local phenom and toured locally with Billy Eckstine's band while he was in high school. He moved to New York under the guise of attending the Julliard School of Music. However, his real intentions were to hook up with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. He quickly climbed up the ranks while learning from Bird and Diz and became the trumpet player for Charlie Parker's group for nearly 3 years. His first attempt at leading a group came in 1949 and was the first of many occurrences in which he would take jazz in a new direction. Along with arranger Gil Evans, he created a nonet (9 members) that used non-traditional instruments in a jazz setting, such as French horn and Tuba. He invented a more subtle, yet still challenging style that became known as "cool jazz." This style influenced a large group of musicians who played primarily on the west coast and further explored this style. The recordings of the nonet were packaged by Capitol records and released under the name The Birth of the Cool. The group featured Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, and Max Roach, among others. This was one of the first instances in which Miles demonstrated a recurring move that angered some: he brought in musicians regardless of race. He once said he'd give a guy with green skin and "polka-dotted breath" a job, as long as they could play sax as well as Lee Konitz. After spending 4 years fighting a heroin addiction, he conquered it, inspired by the discipline of the boxer Sugar Ray Robinson.

Around Midnight at the 1955 Newport Jazz Festival, Miles became a hot commodity. He put together a permanent quintet that featured John Coltrane, Red Garland, "Philly Joe" Jones, and Paul Chambers. Miles had a gift for hearing the music in his head, and putting together a band of incredible musicians whose contrasting styles could result in meeting the end result he was looking for. He later added a 6th member, Cannonball Adderly and replaced Jones and Garland with Jimmy Cobb and Bill Evans. In the late 50s, his groups popularized modal jazz and changed the direction of jazz again. He made 2 more classics with the Sextet during this time, Milestones and Kind of Blue. After this time, most of his group left to form their own groups. This was a constant during Miles' career--he brought in the best up-and-coming musicians and after playing in his band and getting established, they formed their own groups. Among the bandleaders to have come from Miles band include: John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderly, Red Garland, "Philly" Jo Jones, Bill Evans, Wayne Shorter, Joe Zawinul, (Shorter and Zawinul would go on to form the fusion group Weather Report) Keith Jarrett, Tony Williams, Herbie Hancock, John McGlaughlin, Chick Corea, John Scofield, Kenny Garrett, Mike Stern, and Bob Berg.

During this time, Miles and Gil Evans collaborated again and made another unique record, Sketches of Spain, in which Miles plays Spanish Flamenco music backed by an orchestra. His tone is so beautiful and clear, it almost sounds like his trumpet is singing. After experimenting with different groups for 3 years, Miles, who was in his late 30s (old by jazz standards), fused his group with young players in order to bring in fresh ideas. In 1963, he put together his 2nd legendary quintet: Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and 16 year old drumming protege Tony Williams. For 5 years, this group pushed the limits of freedom and made some fiery jazz! In 1968, Miles brought in Joe Zawinul as a 2nd keyboardist and around this time, started experimenting with electric instruments. He made the classic In a Silent Way and a year later, he added British guitarist John McGloughlin and replaced Tony Williams (who left to form his own band) with Jack DeJohnette, and he took jazz in yet a whole new direction with the record Bitches Brew, in which he fused Rock Music with jazz and went heavily into electric music. This record fired the first shot in the fusion revolution which took jazz to a whole new level of popularity.

In the early 1970s, Miles kept experimenting with the electric instruments and fusing more funk into his music. In 1976, a combination of bad health, cocaine use, and lack of inspiration caused Miles to go into a 5-year retirement. He conquered his cocaine habit, received new inspiration and returned in 1981 and made a series of records that I haven't heard. He did keep pushing music, as he was not one to rest on his laurels and play his old music. He started experimenting more with synthesizers and using studio techniques in his recordings. He won a series of Grammy Awards during this decade and continued turning out sidemen, such as Garrett, Stern, and Berg, listed above. Miles Davis died in 1991

http://www.milesdavis.com/music.asp

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miles_Davis

Wikipedia Excerpt: .......while taking a break outside the famous Birdland nightclub in New York City, Davis was beaten by the New York police and subsequently arrested. Believing the assault to have been racially motivated (it is said he was beaten by a single policeman who was angered by Davis being with a white woman), he attempted to pursue the case in the courts, before eventually dropping the proceedings.

Someone's gotta say it..

Too much effort to post all that junk.

Why not just ask for names, titles of influential works, and brief summary of why you chose them?

| quote: |

| Originally posted by Capitalizt Someone's gotta say it.. Too much effort to post all that junk. Why not just ask for names, titles of influential works, and brief summary of why you chose them? |

| quote: |

| Originally posted by Capitalizt Someone's gotta say it.. Too much effort to post all that junk. Why not just ask for names, titles of influential works, and brief summary of why you chose them? |

.

.

True but is it to much to ask to put a little effort into someone that is an influence??

lazy ass

| quote: |

| Originally posted by LazFX lazy ass  |

I'm simply going to post an article, because it's better written than any ode I could offer.

| quote: |

| Remembering Paul Wellstone Five years ago we lost a politician who fearlessly stood up for the best of progressive ideals. That his positions are now coming into widespread acceptance is a testament of the courage of a man who spoke out for what was true. Ezra Klein | October 25, 2007 | web only Remembering Paul Wellstone  Sen. Paul Wellstone, D-Minn., April 24, 1998. (AP Photo/Joel Page) Five years ago today, at 10:22 in the morning, a Beechcraft King Air 100 plane crashed into the forest about two miles from Eveleth airport, where it was supposed to land. The pilots, trying to navigate through freezing rain and snow, had let the craft's speed slow, its engine calm. The drop in velocity sent the plane into a fatal plummet, taking the lives of all those on board, including one of our greatest political leaders. But that great man was, first and foremost, an organizer, a believer in the power of ordinary individuals. He would be appalled to see his name listed before those of the others who died on that plane. So it won't be. On that day, Sheila Wellstone died, as did Marcia, one of the Wellstones' three children. Will McLaughlin, Tom Lapic and Mary McEvoy perished, all of them working for Wellstone's reelection campaign. The two pilots, Michael Guess and Richard Conry, were killed. As was Paul Wellstone. To say that Wellstone cared about the "little guy" may seem like sentimentalism, a clich�, even a hokey affectation for the purpose of this remembrance. It is not. Before I was ever into politics, before I ever had a blog, or a writing fellowship, I was just another pimply teenager, awkward and insecure and chunky and tentative. My older brother lived in Los Angeles, practicing environmental law and living a life that represented, to me, the pinnacle of commitment to social justice. Every weekend was a farmworker's march or an interfaith dialogue or a community benefit. It was this involvement, I assume, that led him to dive into Bill Bradley's 2000 presidential campaign ("Keep studying," Bradley wrote when my brother asked him to autograph a note for me), where he served as Bradley's driver in Los Angeles. Which, one weekend, had him driving around Paul Wellstone. I had no idea who Wellstone was. For that matter, I have no idea why Gideon wasn't more embarrassed of his dorky sibling, why he asked me along for a day with a senator. But he did. We drove all day, through LA traffic, to senior citizen centers and various speeches. Wellstone and his wife gulped down foil-wrapped burritos in the middle of it. And inching through the Southern California haze, we talked. Wellstone had been a champion wrestler in Minnesota. I was a mediocre wrestler at University High School, in Irvine, California. And that's what he wanted to hear about. Not poll numbers or politics, presidents or power. Wrestling. His interest was humbling, and somehow, ennobling. In retrospect, it was, in no small part his kindness, evident generosity of spirit, and commitment to public life, that made me start thinking differently about politics. My protective teenage cynicism was no match for his effortless conviction. He robbed me of my excuse for apathy. Wellstone's populism was not an affectation, or a political posture. It was laced into the fabric of his personality. It's what made him different than other politicians. His measuring stick was not the poll numbers, not the editorial pages, not the political prognosticators, not the Sunday shows -- it was the farmers, the students, the seniors, the people. His fealty to them explains his frequent lonesomeness in the Senate. When the people are your judges, you can stand against the Iraq War in an election year, you can lose votes 99-1. You can fail to pass legislation, because you know the compromise would fail your constituents. "Politics is not about power," he would say. "Politics is not about money. Politics is not about winning for the sake of winning. Politics is about the improvement of people's lives. It's about advancing the cause of peace and justice in our country and the world. Politics is about doing well for the people." Because of this, Wellstone had an immunity to the political trends that few politicians exhibit. When liberal was an epithet, Paul Wellstone wrote a book called The Conscience of a Liberal. When unions were in deep decline, Wellstone stood with them, and now the AFL-CIO now gives an annual award in his honor. After the Clinton health plan was crushed and Democrats retreated from health reform, Wellstone pushed for single-payer. While Clinton was chasing dollars to outspend and overwhelm Bob Dole, Wellstone was calling for full public financing. When progressives were marginalized and cowed by the right's cynical use of 9/11, Wellstone stood on the floor of the Senate, deep within the chambers of power, at the epicenter of cowardice and "responsible" hawkery, and roared on behalf of our ideals. That they were politically inconvenient never deterred him. "If we don't fight hard enough for the things we stand for," he said, "at some point we have to recognize that we don't really stand for them." The fight is not so lonely anymore. Democrats control both houses of Congress. The country now sees George W. Bush much as Wellstone described him. New York Times op-ed columnist Paul Krugman just wrote a book called Conscience of a Liberal, as clear a signal as any of the word's restoration. Economic inequality, wage stagnation, and the health care crisis dominate the Democrats' domestic agenda, just as Wellstone always said they should. It's easier to be a liberal today, to be a progressive, to be proud. But there was a time when it wasn't. When liberalism in defense of peace was mocked, and moderation in service of imperialism was praised. In those days, it was hard to be a liberal. It must have been hard to be Paul Wellstone. He never showed it, though. He liked to quote Marcia Timmel. "I'm so small and the darkness is so great," she said. "We must light a candle," Wellstone would reply. He was ours. Would that he was here to enjoy the dawn. |

Since we live in the world of google I'm only going to put down names (and more for the obscure ones). Maybe some descriptions...

PS. For me Read = read the words, studied = took a long time and wrote notes while reading.

Adam Smith - If you can get through it he's good. It's worth doing so you can see where all the people mis-quote him. I've heard his 'Theory of Moral Sentiment' is actually a better work then 'Wealth of Nations'. I've only partly read wealth.

John M. Keynes - Especially fitting due to the wave of market manipulation by governments in the past two months (year?). I've read his 'General Theory of Employment, Intrest, and Money' but I want to study it if I can get some time at work to do so. He makes reference to his other book a lot.

Kurt Vonogut Jr. - Selected works. I liked 'Slaughter house five', 'Player Piano', and 'Cat's Cradle' a lot. I still haven't read 'Breakfast of Champions'.

Jane Jacobs - Urban Economist - I'd suggest 'Dark Age Ahead' right now. Her monumental works were 'The Death and Life of Great American Cities' and 'The Economics of Cities', both written in the '60s. She was a great advocate of observational studying and refuted many state of the art researchers sucessfully dispite her lack of credentials.

Richard Florida - Economic Geographer - The first living reference I've got. His break through work is 'Rise of the Creative Class'. It describes his observations of the emerging economy and the primacy of knowledge, creativity, and innovation in makeing a region sucessful.

Robertson Davies - Author - A great writer of trilogies. A master of characters and settings.

| quote: |

| Originally posted by atbell Adam Smith - If you can get through it he's good. It's worth doing so you can see where all the people mis-quote him. I've heard his 'Theory of Moral Sentiment' is actually a better work then 'Wealth of Nations'. I've only partly read wealth. |

| quote: |

| The necessaries of life occasion the great expense of the poor. . . . The luxuries and vanities of life occasion the principal expense of the rich, and a magnificent house embellishes and sets off to the best advantage all the other luxuries and vanities which they possess. . . . It is not very unreasonable that the rich should contribute to the public expense, not only in proportion to their revenue, but something more than in that proportion. |

| quote: |

| Originally posted by Lebezniatnikov I couldn't resist this quote from Adam Smith: http://www.newyorker.com/talk/comme...7taco_talk_coll |

.

.

| quote: |

| Originally posted by shaolin_Z Hehe, I bet that will drive many of the Capitalists here nuts. Nice find  . . |

Paul Feyerabend

( >> January 13, 1924 - February 11, 1994 << )

"'Anything goes' is not the one and only 'principle' of a new methodology, recommended by me. It is the only way in which those firmly committed to universal standards and wishing to understand history in their terms can describe my account of traditions and research practices ... If this account is correct then all a rationalist can say about science (and about any other interesting activity) is: anything goes" - Paul Feyerabend

Feyerabend attended a Realgymnasium (High School) at which he was taught Latin, English, and science. He was a Vorzugssch�ler, that is, �a student whose grades exceeded a certain average� (p. 22), and by the time he was sixteen he had the reputation of knowing more about physics and math than his teachers. But he also got thrown out of school on one occasion.

Feyerabend �stumbled into drama� (p. 26) by accident, becoming something of a ham actor in the process. This accident then led to another, when he found himself forced to accept philosophy texts among the bundles of books he had bought for the plays and novels they contained. It was, he later claimed, �the dramatic possibilities of reasoning and� the power that arguments seem to exert over people� (p. 27) with which philosophy fascinated him. Although his reputation was as a philosopher, he preferred to be thought of as an entertainer. His interests, he said, were always somewhat unfocussed (p. 27).

However, Feyerabend's school physics teacher Oswald Thomas inspired in him an interest in physics and astronomy. The first lecture he gave (at school) seems to have been on these subjects (p. 28). Together with his father, he built a telescope and �became a regular observer for the Swiss Institute of Solar Research� (p. 29). He describes his scientific interests as follows:

I was interested in both the technical and the more general aspects of physics and astronomy, but I drew no distinction between them. For me, Eddington, Mach (his Mechanics and Theory of Heat), and Hugo Dingler (Foundations of Geometry) were scientists who moved freely from one end of their subject to the other. I read Mach very carefully and made many notes. (p. 30).

Feyerabend does not tell us how he became acquainted with another one of his main preoccupations�singing. He was proud of his voice, becoming a member of a choir, and took singing lessons for years, later claiming to have remained in California in order not to have to give up his singing teacher. In his autobiography he talks of the pleasure, greater than any intellectual pleasure, derived from having and using a well-trained singing voice (p. 83). During his time in Vienna in the second world war, his interest led him to attend the opera (first the Volksoper, and then the Staatsoper) together with his mother. A former opera singer, Johann Langer, gave him singing lessons and encouraged him to go to an academy. After passing the entrance examination, Feyerabend did so, becoming a pupil of Adolf Vogel. At this point in his life, he later recalled:

The course of my life was� clear: theoretical astronomy during the day, preferably in the domain of perturbation theory; then rehearsals, coaching, vocal exercises, opera in the evening�; and astronomical observation at night� The only remaining obstacle was the war. (p. 35).

(...)

2.12 The Late Sixties

During the summer of 1966, Feyerabend lectured on church dogma at Berkeley. (�Why church dogma? Because the development of church dogma shares many features with the development of scientific thought� (pp. 137�8)). He eventually turned these thoughts into a paper on �Classical Empiricism�, published in 1970, in which he argued that empiricism shared certain problematic features with protestantism. He had already come some way from his 1965 defence of a �disinfected�, �tolerant� form of Empiricism. The publication, in 1969, of the four-page article, �Science Without Experience�, which argued that in principle experience is necessary at no point in the construction, comprehension or testing of empirical scientific theories finally gave notice that Feyerabend was no longer concerned to present himself as any kind of empiricist.

Despite taking his academic duties and responsibilities decreasingly seriously, and coming into conflict with his own university's administration as a result, Feyerabend had not yet fouled his substantial reputation as a serious philosopher of science. He reports that he received job offers from London, Berlin, Yale, and Auckland, that he was invited to become a fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, and that he corresponded with Friedrich von Hayek (whom he already knew from the Alpbach seminars) about a job in Freiburg (p. 127). He accepted the posts in London, Berlin, and Yale. In 1968, he resigned from UC Berkeley and left for Minneapolis, but grew homesick, got re-appointed, and returned to Berkeley almost immediately.

In London, lecturing to University College and the LSE, he met Imre Lakatos. The two became great friends, corresponding with one another regularly and voluminously until Lakatos' death. Feyerabend recalls that Lakatos, whose office was across the corridor from the LSE lecture hall, used to intervene in his lectures when Feyerabend made a point he disagreed with (SFS, p. 13, KT, p. 128).

2.13 Against Method (1970�75)

After stints in London, Berlin, and Yale (all of them running alongside his post at UC Berkeley), Feyerabend took up a chair at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, and lectured there in 1972 and 1974 (pp. 134�5). He even considered settling down in New Zealand around that time (p. 153), although this hardly seems compatible with his jet-setting lifestyle.

By the early 1970s Feyerabend had flown the falsificationist coop and was ready expound his own perspective on scientific method. In 1970, he published a long article entitled �Against Method� in which he attacked several prominent accounts of scientific methodology. In their correspondence, he and Lakatos subsequently planned the construction of a debate volume, to be entitled For and Against Method, in which Lakatos would put forward the �rationalist� case that there was an identifiable set of rules of scientific method which make all good science science, and Feyerabend would attack it. Lakatos' unexpected death in February 1974, which seems to have shocked Feyerabend deeply, meant that the rationalist part of the joint work was never completed.

Later that year, Feyerabend found himself lecturing at the University of Sussex:

I have no idea why and how I went to the University of Sussex at Brighton� what I do remember is that I taught two terms (1974/1975) and then resigned; twelve hours a week (one lecture course, the rest tutorials) was too much. (p. 153).

A member of Feyerabend's audience recalls things in rather more detail:

Sussex University: the start of the Autumn Term, 1974. There was not a seat to be had in the biggest Arts lecture theatre on campus. Taut with anticipation, we waited expectantly and impatiently for the advertized event to begin. He was not on time�as usual. In fact rumour had it that he would not be appearing at all that illness (or was it just ennui? or perhaps a mistress?) had confined him to bed. But just as we began sadly to reconcile ourselves to the idea that there would be no performance that day at all, Paul Feyerabend burst through the door at the front of the packed hall. Rather pale, and supporting himself on a short metal crutch, he walked with a limp across to the blackboard. Removing his sweater he picked up the chalk and wrote down three questions one beneath the other: What's so great about knowledge? What's so great about science? What's so great about truth? We were not going to be disappointed after all!

During the following weeks of that term, and for the rest of his year as a visiting lecturer, Feyerabend demolished virtually every traditional academic boundary. He held no idea and no person sacred. With unprecedented energy and enthusiasm he discussed anything from Aristotle to the Azande. How does science differ from witchcraft? Does it provide the only rational way of cognitively organizing our experience? What should we do if the pursuit of truth cripples our intellects and stunts our individuality? Suddenly epistemology became an exhilarating area of investigation.

Feyerabend created spaces in which people could breathe again. He demanded of philosophers that they be receptive to ideas from the most disparate and apparently far-flung domains, and insisted that only in this way could they understand the processes whereby knowledge grows. His listeners were enthralled, and he held his huge audiences until, too ill and too exhausted to continue, he simply began repeating himself. But not before he had brought the house down by writing �Aristotle� in three-foot high letters on the blackboard and then writing �Popper� in tiny, virtually illegible letters beneath it! (John Krige, Science, Revolution and Discontinuity, (Sussex: Harvester Press, 1980), pp. 106�7).

Because his health was poor, Feyerabend started seeing a healer who had been recommended to him. The treatment was successful, and thenceforth Feyerabend used to refer to his own case as an example of both the failures of orthodox medicine and the largely unexplored possibilities of �alternative� or traditional remedies.

Instead of the volume written jointly with Lakatos, Feyerabend put together his tour de force, the book version of Against Method (London: New Left Books, 1975), which he sometimes conceived of as a letter to Lakatos (to whom the book is dedicated). A more accurate description, however, is the one given in his autobiography:

AM is not a book, it is a collage. It contains descriptions, analyses, arguments that I had published, in almost the same words, ten, fifteen, even twenty years earlier� I arranged them in a suitable order, added transitions, replaced moderate passages with more outrageous ones, and called the result �anarchism�. I loved to shock people� (pp. 139, 142).

The book contained many of the themes mentioned so far in this essay, sprinkled into a case study of the transition from geocentric to heliocentric astronomy. But whereas he had previously been arguing in favour of methodology (a �pluralistic� methodology, that is), he had now become dissatisfied with any methodology. He emphasised that older scientific theories, like Aristotle's theory of motion, had powerful empirical and argumentative support, and stressed, correlatively, that the heroes of the scientific revolution, such as Galileo, were not as scrupulous as they were sometimes represented to be. He portrayed Galileo as making full use of rhetoric, propaganda, and various epistemological tricks in order to support the heliocentric position. The Galileo case is crucial for Feyerabend, since the �scientific revolution� is his paradigm of scientific progress and of radical conceptual change, and Galileo is his hero of the scientific revolution. He also sought further to downgrade the importance of empirical arguments by suggesting that aesthetic criteria, personal whims and social factors have a far more decisive role in the history of science than rationalist or empiricist historiography would indicate.

Against Method explicitly drew the �epistemological anarchist� conclusion that there are no useful and exceptionless methodological rules governing the progress of science or the growth of knowledge. The history of science is so complex that if we insist on a general methodology which will not inhibit progress the only �rule� it will contain will be the useless suggestion: �anything goes�. In particular, logical empiricist methodologies and Popper's Critical Rationalism would inhibit scientific progress by enforcing restrictive conditions on new theories. The more sophisticated �methodology of scientific research programmes� developed by Lakatos either contains ungrounded value-judgements about what constitutes good science, or is reasonable only because it is epistemological anarchism in disguise. The phenomenon of incommensurability renders the standards which these �rationalists� use for comparing theories inapplicable. The book thus (understandably) had Feyerabend branded an �irrationalist�. At a time when Kuhn was downplaying the �irrationalist� implications of his own book, Feyerabend was perceived to be casting himself in the role others already saw as his for the taking. (He did not, however, commit himself to political anarchism. His political philosophy was a mixture of liberalism and social democracy).

He later said:

One of my motives for writing Against Method was to free people from the tyranny of philosophical obfuscators and abstract concepts such as �truth�, �reality�, or �objectivity�, which narrow people's vision and ways of being in the world. Formulating what I thought were my own attitude and convictions, I unfortunately ended up by introducing concepts of similar rigidity, such as �democracy�, �tradition�, or �relative truth�. Now that I am aware of it, I wonder how it happened. The urge to explain one's own ideas, not simply, not in a story, but by means of a �systematic account�, is powerful indeed. (pp. 179�80).

2.14 The Political Consequences of Epistemological Anarchism: Science in a Free Society (1978)

The critical reaction to Against Method seems to have taken Feyerabend by surprise. He was shocked to be accused of being aggressive and nasty, so he replied by accusing his accusers of the very same thing. He felt it necessary to respond to most of the book's major reviews in print, and later assembled these replies into a section of his next book, Science in a Free Society, entitled �Conversations with Illiterates�. Here he berated the unfortunate reviewers for having misread Against Method, as well as for being constitutionally incapable of distinguishing between irony, playfulness, argument by reductio ad absurdum, and the (apparently rather few) things he had really committed himself to in AM. The spectacle of Feyerabend levelling these accusations at others is not itself without irony. (His widow reports that in his later years, SFS was the book he would most like to have distanced himself from). In the commotion surrounding AM, Feyerabend succumbed to depression:

� now I was alone, sick with some unknown affliction; my private life was in a mess, and I was without a defense. I often wished I had never written that fucking book. (KT, p. 147).

Feyerabend saw himself as having undermined the arguments for science's privileged position within culture, and much of his later work was a critique of the position of science within Western societies. Because there is no scientific method, we can't justify science as the best way of acquiring knowledge. And the results of science don't prove its excellence, since these results have often depended on the presence of non-scientific elements, science prevails only because �the show has been rigged in its favour� (SFS, p. 102), and other traditions, despite their achievements, have never been given a chance. The truth, he suggests, is that

science is much closer to myth than a scientific philosophy is prepared to admit. It is one of the many forms of thought that have been developed by man, and not necessarily the best. It is conspicuous, noisy, and impudent, but it is inherently superior only for those who have already decided in favour of a certain ideology, or who have accepted it without ever having examined its advantages and its limits (AM, p. 295).

The separation of church and state should therefore be supplemented by the separation of science and state, in order for us to achieve the humanity we are capable of. Setting up the ideal of a free society as �a society in which all traditions have equal rights and equal access to the centres of power� (SFS, p. 9), Feyerabend argues that science is a threat to democracy. To defend society against science we should place science under democratic control and be intensely sceptical about scientific �experts�, consulting them only if they are controlled democratically by juries of laypeople.

2.15 Ten Wonderful Years: The Eighties in Berkeley and Zurich

Out of all Feyerabend's many academic positions, perhaps the one he enjoyed most was his tenure throughout the 1980s at the Eidgen�ssische Technische Hochschule, Zurich. Feyerabend applied for the post after his friend Eric Jantsch had told him that the Polytechnic was looking for a philosopher of science. The selection process was, by Feyerabend's account, very long and somewhat involved (pp. 154ff.). Having recently left another post in Kassel, he apparently gave up hopes of being hired by the Swiss, and �decided to remain in Berkeley and stop moving about� (p. 158). But, after several stages in the decision-making procedure, he was finally given the job, and �ten wonderful years of half-Berkeley, half-Switzerland� (p. 158) turned out to be exactly what he had been looking for. At Zurich he lectured on Plato's Theaetetus and Timaeus, and then on Aristotle's Physics. The two-hour seminars, many of which were organised by Christian Thomas (with whom Feyerabend was to edit anthologies) were run on the same lines as Berkeley: no set topic, but presentations by the participants (p. 160). Feyerabend later considered this to be the period in which he �got his intellectual act together� (p. 162), meaning that he recovered from the critical reactions to Against Method and was finally freed from the necessity of defending it against all criticism. However, this didn't seem to have affected his attitude towards work: in Zurich he refused offers of an office, because no office meant no office hours, and therefore no waste of time (pp. 131, 158)!

Many of the more important papers Feyerabend published during the mid-1980s were collected together in Farewell to Reason (London: Verso, 1987). The major message of this book is that relativism is the solution to the problems of conflicting beliefs and of conflicting ways of life. Feyerabend starts by suggesting that the contemporary intellectual scene in Western culture is by no means as fragmented and cacophonous as many intellectuals would have us believe. The surface diversity belies a deeper uniformity, a monotony generated and sustained by the cultural and ideological imperialism which the West uses to beat its opponents into submission. Such uniformity, however, can be shown to be harmful even when judged by the standards of those who impose it. Cultural diversity, which already exists in some societies, is a good thing not least because it affords the best defence against totalitarian domination.

Feyerabend proposes to support the idea of cultural diversity both positively, by producing considerations in its favour, and negatively �by criticising philosophies that oppose it� (FTR, p. 5). Contemporary philosophies of the latter type are said to rest on the notions of Objectivity and Reason. He seeks to undermine the former notion by pointing out that confrontations between cultures with strongly held opinions which are each believed by members of the cultures in question to be objectively true can turn out in different ways. The result of such confrontation may be the persistence of the old views, fruitful and mutual interaction, relativism, or argumentative evaluation. �Relativism� here means the decision to treat the other people's form of life and the beliefs it embodies as �true-for-them�, while treating our own views as �true-for-us�. Feyerabend feels that this is an appropriate way to resolve such confrontation.

Admittedly, these outcomes are indeed possible. But this does not establish any form of relativism. Indeed, we might as well turn the argument around, and say that the possibility of the dispute being resolved by one participant freely coming around to the other's point of view shows the untenability of relativism.

Feyerabend complains that the ideas of reason and rationality are �ambiguous and never clearly explained� (FTR, p. 10); they are deified hangovers from autocratic times which no longer have any content but whose �halo of excellence� (ibid.) clings to them and lends them spurious respectability:

[R]ationalism has no identifiable content and reason no recognisable agenda over and above the principles of the party that happens to have appropriated its name. All it does now is to lend class to the general drive towards monotony. It is time to disengage Reason from this drive and, as it has been thoroughly compromised by the association, to bid it farewell. (FTR, p. 13).

Relativism is the tool with which Feyerabend hopes to �undermine the very basis of Reason� (ibid.). But is it Reason with a capital �R�, the philosophers' abstraction alone, that is to be renounced, or reason itself too? Feyerabend is on weak ground when he claims that �Reason� is a philosophers' notion which has no content, for it is precisely the philosopher who is willing to attach a specific content to the formal notion of rationality (unlike the layperson, whose notion of reason is closer to what Feyerabend calls the �material� conception, where to be rational is �to avoid certain views and to accept others� (ibid., p. 10)).

Relativism is a result of cultural confrontation, an �attempt to make sense of the phenomenon of cultural variety� (FTR, p. 19). Feyerabend is well aware that the term �relativism� itself is understood in many different ways. But his attempt to occupy a substantial yet defensible relativist position is a failure. At some points he merely endorses views which no-one would deny, but which do not deserve to be called relativist (such as the idea that people may profit from studying other points of view, no matter how strongly they hold their own view (FTR, p. 20)). At others he does manage to subscribe to a genuinely relativist view, but fails to show why it must be accepted.

It was only in 1988, on the 50th anniversary of Austria's unification with Germany, that Feyerabend became interested in his past (p. 1). The Feyerabends left California for life in Switzerland and Italy in the fall of 1989 (p. 2). It was during this move that Feyerabend re-discovered his mother's suicide note (p. 9), which may have been one of the factors that spurred him to write his autobiography. Feyerabend looked forward to his retirement, and he and Grazia decided to try to have children. He claimed to have forgotten the thirty-five years of his academic career almost as quickly as he had earlier forgotten his military service (p. 168).

2.16 Feyerabend in the Nineties

Feyerabend published a surprisingly large number of papers in the 1990s (although many of them were short ones with overlapping content). Several appeared in a new journal, Common Knowledge, in whose inauguration he lent a hand, and which set out to integrate insights from all parts of the intellectual landscape.

Although these papers were on scattered subjects, there are some strong themes running through them, several of which bear comparison with what gets called �post-modernism� (see Preston [forthcoming]). Here I shall sketch only the main ones.

One of the projects which Feyerabend worked on for a long time, but never really brought to completion, went under the name �The Rise of Western Rationalism�. Under this umbrella he hoped to show that Reason (with a capital �R�) and Science had displaced the binding principles of previous world-views not as the result of having won an argument, but as the result of power-play. While the first philosophers (the pre-Socratic thinkers) had interesting views, their attempt to replace, streamline or rationalise the folk-wisdom which surrounded them was eminently resistible. Their introduction of the appearance/reality dichotomy made nonsense of many of the things people had previously known. Even nowadays, indigenous cultures and counter-cultural practices provide alternatives to Reason and that nasty Western science.

However, Feyerabend recognised that this is to present science as too much of a monolith. In most of his work after Against Method, he emphasises what has come to be known as the �disunity of science�. Science, he insists, is a collage, not a system or a unified project. Not only does it include plenty of components derived from distinctly �non-scientific� disciplines, but these components are often vital parts of the �progress� science has made (using whatever criterion of progress you prefer). Science is a collection of theories, practices, research traditions and world-views whose range of application is not well-determined and whose merits vary to a great extent. All this can be summed up in his slogan: �Science is not one thing, it is many.�

Likewise, the supposed ontological correlate of science, �the world�, consists not only of one kind of thing but of countless kinds of things, things which cannot be �reduced� to one another. In fact, there is no good reason to suppose that the world has a single, determinate nature. Rather we inquirers construct the world in the course of our inquiries, and the plurality of our inquiries ensures that the world itself has a deeply plural quality: the Homeric gods and the microphysicist's subatomic particles are simply different ways in which �Being� responds to (different kinds of) inquiry. How the world is �in-itself� is for ever unknowable. In this respect, Feyerabend's last work can be thought of as aligned with �social constructivism�.

2.17 Conclusion: Last Things

Feyerabend's autobiography occupied him right up until his death on February 11th, 1994, at the Genolier Clinic, overlooking Lake Geneva. At the end of the book, he expressed the wish that what should remain of him would be �not papers, not final declarations, but love� (p. 181).

His autobiography was published in 1995, a third volume of his Philosophical Papers appeared in 1999, and his last book The Conquest of Abundance, , edited by Bert Terpstra, appeared in the same year. A volume of his papers on the philosophy of quantum mechanics is currently being prepared, under the editorship of Stefano Gattei.

Although the focus of philosophy of science has moved away from interest in scientific methodology in recent years, this is not due in any great measure to acceptance of Feyerabend's anti-methodological argument. His critique of science (which gave him the reputation for being an �anti-science philosopher�, �the worst enemy of science�, etc.) is patchy. Its flaws stem directly from his scientific realism. It sets up a straight confrontation between science and other belief-systems as if they are all aiming to do the same thing (give us �knowledge of the world�) and must be compared for how well they deliver the goods. A better approach would be, in Gilbert Ryle's words, �to draw uncompromising contrasts� between the businesses of science and those of other belief-systems. Such an approach fits far better with the theme Feyerabend approached later in his life: that of the disunity of science.

Feyerabend came to be seen as a leading cultural relativist, not just because he stressed that some theories are incommensurable, but also because he defended relativism in politics as well as in epistemology. His denunciations of aggressive Western imperialism, his critique of science itself, his conclusion that �objectively� there may be nothing to choose between the claims of science and those of astrology, voodoo, and alternative medicine, as well as his concern for environmental issues ensured that he was a hero of the anti-technological counter-culture.

Different components and phases of Feyerabend's work have influenced very different groups of thinkers. His early scientific realism, contextual theory of meaning, and the way he proposed to defend materialism were taken up by Paul and Patricia Churchland. Richard Rorty, for a time, also endorsed eliminative materialism. Feyerabend's critique of reductionism has influenced Cliff Hooker and John Dupr�, and his general point of view influenced books such as Alan Chalmers' well-known introduction to philosophy of science What is this thing called science? (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1978).

Feyerabend has also had considerable influence within the social studies. He directly inspired books like D.L.Phillips' Abandoning Method (San Francisco, 1973), in which the attempt was made to transcend methodology. Less directly, he has exerted enormous influence on a generation of sociologists of science through his relativism, social constructivism, and apparent irrationalism. It is still far too early to say whether, and in what way, his philosophy will be remembered. [ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy ]

[ Wikipedia ]

Wikipedia Excerpt:

"Paul Karl Feyerabend (January 13, 1924 � February 11, 1994) was an Austrian-born philosopher of science best known for his work as a professor of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, where he worked for three decades (1958�1989). His life was a peripatetic one, as he lived at various times in England, the United States, New Zealand, Italy, and finally Switzerland. His major works include Against Method (published in 1975), Science in a Free Society (published in 1978) and Farewell to Reason (a collection of papers published in 1987). Feyerabend became famous for his purportedly anarchistic view of science and his rejection of the existence of universal methodological rules. He is an influential figure in the philosophy of science, and also in the sociology of scientific knowledge."

It's kind of sloppy but here goes nothing. Maybe I'll clean it up a bit when I get more time.

Aldous Leonard Huxley

(26 July 1894 � 22 November 1963)

| quote: |

| The really hopeless victims of mental illness are to be found among those who appear to be most normal. "Many of them are normal because they are so well adjusted to our mode of existence, because their human voice has been silenced so early in their lives, that they do not even struggle or suffer or develop symptoms as the neurotic does." They are normal not in what may be called the absolute sense of the word; they are normal only in relation to a profoundly abnormal society. Their perfect adjustment to that abnormal society is a measure of their mental sickness. These millions of abnormally normal people, living without fuss in a society to which, if they were fully human beings, they ought not to be adjusted, still cherish "the illusion of individuality," but in fact they have been to a great extent deindividualized. Their conformity is developing into something like uniformity. But "uniformity and freedom are incompatible. Uniformity and mental health are incompatible too. . . . Man is not made to be an automaton, and if he becomes one, the basis for mental health is destroyed." - Aldous Huxley, Brave New World Revisited |

| quote: |

| Mindlessness and moral idiocy are not characteristically human attributes; they are symptoms of herd-poisoning. - Aldous Huxley, Brave New World Revisited |

| quote: |

| There will be, in the next generation or so, a pharmacological method of making people love their servitude, and producing dictatorship without tears, so to speak, producing a kind of painless concentration camp for entire societies, so that people will in fact have their liberties taken away from them, but will rather enjoy it, because they will be distracted from any desire to rebel by propaganda or brainwashing, or brainwashing enhanced by pharmacological methods. And this seems to be the final revolution. - Aldous Huxley, at a lecture given to the Tavistock Group, California Medical School, June 27, 1961 full transcript audio stream (Real Media) |

Robert Anton Wilson

http://deoxy.org/raw.htm

http://www.rawilson.com/home.html

One of the most amazing minds...

Too tired to make a large post at this time, but suffice to say Carl Sagan. Had some incredibly insightful views about the world let alone his knowledge of science.

![]() Please Share

Please Share

http://www.quickmeme.com/meme/3qyd55/

Powered by: vBulletin

Copyright © 2000-2021, Jelsoft Enterprises Ltd.